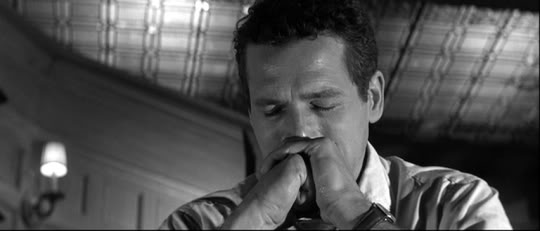

Jack Lemmon, Shirley MacLaine, Fred MacMurray

Directed by Billy Wilder

Written by Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond

The Apartment, critical and commercial smash hit of 1960, is the progenitor to the romantic comedy and one the most perfect movies of its era, both in plot and in its characters.

After viewing the classic Brief Encounter in 1944, The Apartment director Billy Wilder had to wait more than a decade before film codes could relax enough for him to tell the story of the “third man”, the friend who lets reluctant but star-crossed lovers Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson use his flat for their brief encounters.

In his vision 14 years later enters the character of bachelor C.C. Baxter (Lemmon), a low-level worker in a giant New York insurance company, who is on the rise only because he generously lets out his swank apartment for use by his promiscuous bosses and their mistresses.

It’s such a lucrative business that he has to arrange these “meetings” in his day planner, to the point where most nights he sleeps in Central Park or doesn’t sleep at all. At work he flirts continuously with Miss Kubelik (MacLaine), the elevator operator with whom he is hopelessly smitten with, and he finally gets the chance for promotion when smarmy director Sheldrake (MacMurray) invites him to his office and asks if he can borrow the keys for the night.

It’s revealed to the audience that Sheldrake’s lover for the night is none other than Miss Kubelik, who is silly enough to believe Sheldrake’s promises of divorcing his wife and marrying her. Her realization that he is a liar causes her to nearly commit suicide by taking sleeping pills, a deed undone by the arrival of Baxter, who brings a bar girl to his apartment only to find Sheldrake gone and poor Miss Kubelik comatose on his bed. He revives her with the help of his Jewish doctor neighbor, and Baxter spends a few days in heaven taking care of her before they have to go back to their separate lives.

This sets the stage for the conclusion’s questions – whether or not Miss Kubelik will choose suave but untruthful Sheldrake or wholesome but goofy Baxter – and the ending is as resolutely satisfying as it is sweet.

Lemmon, easily in the top tier of all-time American actors, adds his considerable comedic talent to a dramatic role that required a sensitive, well-meaning jokester. How natural his acting is, and the way he chooses to deliver his dialogue’s lines are inimitable, while his ad-libs of some of Wilder and I.A.L Diamond’s screenplay were so pitch-perfect that they replaced the original script’s lines.

MacLaine stole several filmgoers’ hearts as the cute and vulnerable, pixie-like Miss Kubelik, who not only holds her own against both of the wildly-different male actors, but creates a zestful chemistry with Lemmon throughout the picture.

The film’s theme, written by Charles Williams, is a beautiful sweeping melody, which at first seemed over-the-top considering the comedic element in the first hour. But tackling the previously unheard-of themes in a major picture – like flagrant, encouraged infidelity and attempted suicide – the score takes on more meaning and accompanies The Apartment’s lovely ending perfectly.

Of all of the romantic dramas of that decade, no male lead is more believable and real than Lemmon’s C.C. Baxter, and very few films have been as perfect a comedy-drama at The Apartment.

Images courtesy of brittanica.com and vintagefilm.typepad.com, respectively.

You must be logged in to post a comment.